And world number ten female surfer Isabella Nichols “came out as transgender in 2021”

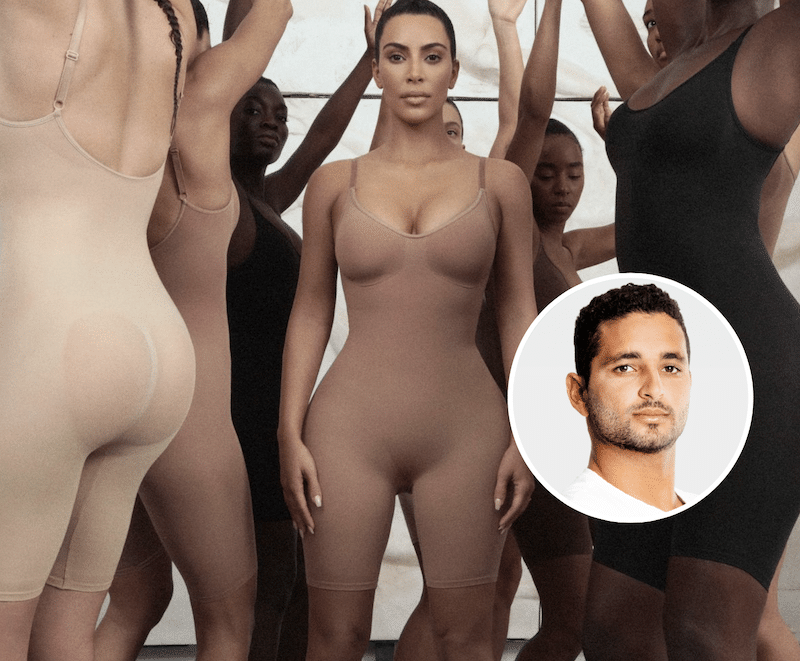

There’s a few people you don’t fool around with in the surf world and at the top of the list, I would think and would challenge anyone to argue against, is the Kauai-born jiujitsu world champion and noted North Shore enforcer Kai “Kaiborg” Garcia.

Garcia is the former minder of Bruce and Andy Irons; a surfer and grappler whose bona fides, either on the mat or amid the heaviest waves in the world, need no further emphasis.

I went back a little earlier today to see if the much vaunted AI bots had learned from their mistake.

Well, yeah and nope.

Tia Blanco is “not non-binary” but Keala is still in there along with world number ten women’s surfer Isabella Nichols “who came out as transgender in 2021” and Kaiborg who “is a transgender surfer and surf instructor from Hawaii who has been featured in a number of surfing publications. Kai is also an advocate for LGBTQ+ rights and is involved with several organizations that support the community.”

Kaiborg is a lot of things: big-wave shredder, inspiration to thousands, a formidable roll in the gym, a daddy, but he ain’t no tranny.

If you really want to get to know Kaiborg, dive into Chas Smith’s Welcome to Paradise Now Go to Hell, buy here, free shipping etc)

Too cheap to buy?

Read the Borg chapter here.

I have arrived back on the North Shore, fresh from Honolulu and a piña colada, momentary respite, and a revelation that maybe this is all really and truly paradise. That is the violence and commitment to violence by wave and men that makes it such. I have passed all the familiar landmarks and I am ready to get my head fucking cracked as a personal ablution. I always imagined that I wanted peace and tranquility and a garden and Saint Bernard. But I am defective. I have had traditional peace. I have owned a wonderful little prewar house in hipster Eagle Rock, Los Angeles, with the wife that I hated, and we had a Saint Bernard and I would come home from near-death Middle East experiences and think, “Never again.” I would rub my Saint on his big fluffy head and think, “I have done enough.” But three weeks later I would be thinking about adventure and five weeks later I would be on an adventure, running from Arabs holding rifles. Sweating. Cursing. Damn me. Damn my own degenerate heart. But maybe not. Maybe this is all the way, the truth, the life. Whatever. Even today I want to go climb Mount Everest to prove that it is not very difficult and the people that I love very much do not want me to but I will anyhow because I cannot stop.

And so I passed Waimea, I passed Foodland, and I passed the Billabong house before slamming my car onto the shoulder in front of Sunset Beach Elementary School and thinking about an adventure with Kaiborg. I needed his story. He told me, once, when we talked about Andy Irons, that whatever I needed he would give me. I wanted to push this further. To see if there is more to feel on the North Shore. To see if I can fall even further down the rabbity hole. To see if I can get further consumed, as if I am not consumed enough already. I had turned the radio from Top 40 to a Hawaiian station and Israel Kamakawiwo’ole, or Bruddah Iz to da locals, is singing a ukulele cover. “Somewhere over the rainbow, way up high, and the dreams that you dream of once in a lullaby . . .”

The contest had just ended for the day and would commence again early tomorrow morning but there were parties to be had and the road was full with fans and surfers trying to decide what to do. What their next steps should be. I push through them toward the small sand trail and stood between the two Volcom houses. Their gates flank me like zombies who would eat my brains. I decide to go into the original house gate. I pull the lock and enter and feel cold and not well.

I cannot see Kaiborg but do see a derelict sitting on the deck hooting at the surfers in the water. Anytime a contest ends tens, maybe hundreds, of surfers huddle on the shoulder until the final horn and then they scramble to the peak, trying to catch the first wave of the postcontest day. Today there are maybe fifty surfers scrambling around, dropping in, getting spit out. And the derelict hoots them. “Whoooooohooooo!” I ask him where Kaiborg is and he responds in two syllables, “‘A’ house,” without looking my way. He is not Hawaiian but old enough to be the sort of non-Hawaiian clown grandfathered in. He is wearing shorts. And so I leave, kicking a Coors can into the bush before opening the gate back to the sandy path and through the A-team house gate.

The A-team house feels different, nicer, but it is still dark. Its deck is not rotted. Its grass is not trampled to an early death. There are no couches on cinder blocks. I approach and spot a broom and scratch at my feet furiously before moving from grass to wood. I make sure there are no specs of sand this time.

Dean Morrison is sitting on the porch, nursing a beer. He is the smallest Gold Coast surfer, of Maori descent, and cute but also loves his drink. He once used to surf on the World Championship Tour but no longer because he loves his drink and is a bit of a cheater. Once, during last year’s Pipe Masters, he surfed a heat against Damien Hobgood and it was a real scrappy, close heat. Toward the end Damien had priority and a great wave came toward him and he paddled for it. Inexplicably he slipped and went over the falls, awkwardly. It would have been a great wave and Damien might have won but, instead, Dean won. Back on shore Damien found the head judge and started barking about how Dean had actually tugged his leash, sending him over the falls. A dirty move.

And now he nurses his beer on the Volcom A-team house deck. I ask him if Kaiborg is around and he says, “Yeah, he’s inside sleeping. Go wake him up.” I may be many things but I am not totally oblivious. Still, it is tempting. I look through the sliding glass door and see Kaiborg asleep, a sleeping giant, and it feels like being at a zoo and wanting to stick a troublemaking hand into the tiger’s cage. I resist, though, and sit next to Dean instead, and watch Pipe fire and watch the sun slip farther down the sky. It is still too cold but the sunset will be gorgeous for sure. Sunsets on the North Shore are almost always gorgeous.

After fifteen minutes Kaiborg stumbles out onto the porch, scratching his stomach and stretching. He looks out toward Pipe for a long time. He arches his back. He is a giant of a man. As big as a house. Arms like Toyota Land Cruisers. He towers above me because I am sitting next to Dean but he would tower above me even if I was standing. Even though I am slightly taller. And, looking up, Kaiborg blocks the sky. He is all I can see. He is a specimen. He is handsome like a Roman gladiator. “Kai,” I say in my friendly voice, and my friendly voice always grates my ears because my nose has been broken so many times that my friendly voice sounds like a nasal Muppet. “Do you have a minute to talk?” I only like my voice at three a.m. after one pack of Camel Reds and five whiskey sodas. He studies me with freshly woken eyes and then responds, “Hoooo, Chas, yeah brah, let’s go over to the other house.” I am climbing Everest just to do it. Just because I can’t stop. I am entering into the real possibility of big trouble for the sake of getting into big trouble, or maybe to serve my ablution, but I also need to hear more and I don’t know exactly what. I need to feel more. Eddie and Kaiborg in the same wicked day is a real double-down. How can simply talking to another man be so bad? Because this is the North Shore. And asking personal questions is worse.

I follow him through both gates, brushing my feet like a fiend again, before joining him on the cinder block couch.

We both watch the waves, quietly, for a few moments. We watch an unknown surfer get barreled and spit out. We watch a haole paddle awkwardly in the way of a Hawaiian and there will definitely be blood spilt before the sun sets completely. I ask Kaiborg about how it used to be on the North Shore. He looks at me and his voice answers. It is not like Eddie’s. It is not a guttural mess but instead sort of sweet, inflected with the islands. “Ahhhhhh, how do you say . . . those were caveman days. Paleolithic. A trip, brah. This is our spot, our place . . .” he said, referring to the rampant territorialism of surf and of the North Shore “We’d learn from our uncles, who would paddle out and beat the shit out of people and then they’d tell us to beat them up. And we thought that was normal. We didn’t know anything else, you know? Sad to say but it’s just how it was. Not how it is anymore.” Bullshit. Bull fucking shit. The past is always and forever seen as harder, rougher, deadlier, tougher. Grandparents talk about walking to school uphill both ways. Parents talk about the exorbitant cost of shoes and things today. The past is always seen through a different filter and events can take on greater, rougher, better, worse connotations. I was not on the North Shore in those early days. But, truthfully, I have seen more fear in the eyes on the North Shore than anywhere on earth. I can’t imagine more fear than there is today. Kaiborg is wrong. He is accentuating history and minimizing the present. But there is no fucking way I will tell him he is wrong and so I merely respond, “Yeah? Seems pretty rough to me still, I mean . . . ” And he looks over at me, all two hundred fifty muscled pounds of him, and says, “No no no. It’s so different now. Back then there was nobody even around, not near the amount of people that are here today. What we did . . . It was just straight territorial trip. It was . . . back then we thought it was all cool and right on, this is what we do cuz we didn’t know any better, but now that I’m older and look back on it I’m like, whoa. Wow.” I still think bull fucking shit. I believe, full well, that Kaiborg doesn’t crack as many heads today as he used to but that is only because he has done Malcom Gladwell’s ten thousand hours. Malcolm Gladwell quoted neurologist Daniel Levin, in his book Outliers: “The emerging picture from such studies is that ten thousand hours of practice is required with being a world-class expert in anything.” Kaiborg has cracked ten thousand heads and now nobody will mess with him. Or very very few people will mess with him. Word on the coconut wireless is that Kai and Eddie have beef. That they don’t like each other. And also there is another at the Volcom house, Tai Van Dyke, who is looking to take over as big man and run Kaiborg off. Kaiborg used to party. He used to go as wild as anyone. Wilder than maybe everyone, excluding Andy and Bruce. But he has since cleaned up, completely. He doesn’t even drink anymore, and this frustrates some. It frustrates Bruce and so Bruce is on a mission to replace his old great friend with another dark party animal, Tai Van Dyke. Bruce does not hide his contempt, nor his ambition. Kaiborg has a whiteboard where he writes the workout schedule for the groms. After John John won the Triple Crown, Bruce marched downstairs and scrubbed out the workout schedule and wrote, “Big fucking rager tonight,” signing underneath in his own scrawl, “BRUCE IRONS.” A proper affront to the power structure at the Volcom houses. Derek Dunfee, a big-wave surfer from La Jolla, California, sponsored by Volcom, who has done many tour of duties, later told me, “I have never felt it that way at all, that unhinged. Literally. I had my bags packed the entire time I stayed there in case shit really went down. I’ve never done that before but it felt like all-out war was imminent at any moment and I was ready to fucking bail.”

The North Shore has always been rough. It is rough today, and it was rough when Kaiborg first started coming. I ask him when, in fact, he did come first and he answers, “I started coming to the North Shore when I was sixteen. First trip stayed with Marvin Foster. I came with my brother and, like I said, those were the kind of people we looked up to. We looked up to the kind of people that most people don’t look up to. And it was the exact same thing we got thrown in over here like it was over there. But over here we had to prove ourself even more.” Over there is Kauai, where he grew up and where he learned to pound and crack and surf. Marvin Foster was one of the toughest men to ever wander the North Shore. He was a genuine star in the 1980s, charging every oversized swell, but he also got into the drug trade, spending eighteen months in prison in the early 1990s on a weapons charge. He also, later, landed on Hawaii’s top-ten-most-wanted list. Marvin Foster died by hanging himself from a tree in 2010. This was Kaiborg’s moral compass.

But how does it all work? What happens? How does a sixteen-year-old Kauai kid come to the North Shore and become a legend? What did Kaiborg do to prove himself? And so I ask as the sun slides farther and farther down the sky, which continues to fire. Which continues to look like a painting. Kaiborg looks at the sun and lets out a long and low “Psssssssshhhhhhhhhht” before pausing long. How to answer? “Just doing all the wrong things. You know. ‘Doing the work,’ as they like to say now. Doing the dirt for everyone. Like they said, ‘Go lick that guy.’ You gotta do it.” It sounds, to me, like hell. It sounds, to me, like jail and so I ask, “Was it like jail?” And his voice goes very high in response, his head kicks back, and he locks his fingers behind his head. A small smile creeps over his face. “It wasn’t . . . it wasn’t . . . it wasn’t like jail or anything like that because it was all we knew. You know? Like now that I’m older and everything . . . it’s basically like, I don’t live in the past, but I don’t shut the door on it either. When I see people out in the water now or whatever, hey, I’ll start character assassinating but then I’ll check myself and go, ‘Hey, these guys are just out here to have a good time too.’ I ain’t telling nobody to beat it. I ain’t telling . . . I don’t yell at nobody in the water I don’t . . .” He trails off, thinking more. Thinking about his past and what it meant to him and what it means to him. “And that’s all from where I was to where I am. And now I don’t say anything. I do my trip and that’s it. I’m not the most friendly guy in the water but I’m not loudmouthing off or, you know, I’m just out there to get my waves, get my daily reprieve and come in all happy. But, you know, sometimes you gotta put that vibe off out in the water because some people take your kindness for weakness and they’ll start hustling you and, fuck that, brah, you know . . . I don’t know if it’s like, self-entitlement or, whatever, but I’ve put my time in and I’m cherry-picking. I’m not a little kid paddling for every wave. I’m waiting for mine and when they come to me, if you’re behind me, that’s your problem. I’m going. I’m not going to yell at you, or whatever, just don’t drop in on me. And everybody knows the deal.”

No person would ever drop in on Kaiborg, full stop. He is huge and one does not have to be intimately aware of any regional hierarchy to know a huge man is not to be toyed with.

But still, how long does it take for a man, an outsider for that matter, to climb to the top of the North Shore’s very specific, very rough, hierarchy? Eddie came from Philadelphia and climbed to the top in a matter of years. Kaiborg, though, is different. “You’re always climbing ’til today.” And then he chuckles because he is not climbing and maybe he never was. “Nahhh, honestly I can’t say when or what but I’ve never really had a problem because I’ve always been with all the crew. I’ve never been on the short end of the stick, basically. And what that develops, when you start to turn into a young man, is a lot of fucken unwarranted pride and ego. And it’s ugly. That whole mind-frame is just . . . so wrong. That . . . but hey. It’s life. If you don’t know any better and . . . basically we all come from broken homes, the whole shit, so we don’t know the ways like everybody around us, since we were like five, so . . . you’re a product of your environment no matter what. And as you get older, you start learning. The key is to try and break the cycle and not repeat it with where you are with the kids under you because . . . it’s just a shitty fucken thing.”

Kaiborg’s introspection is intriguing. He is here, on the cinder-block-raised couch, in his fiefdom, talking about breaking cycles of violence and the ugliness of ego and being a product of an environment. His fiefdom. It is Eddie’s kingdom, but Kaiborg rules the one thing that matters most. He rules Pipeline. This is not what I expected at all. I expected bravado or harsh vibing or a slap or aggressive platitudes about respect and such. But he seems so Zen and what he is saying seems genuine. Or maybe I have been totally and completely consumed and violent nonsense is now completely reasonable. I tell him he is a Zen thug and he laughs. “You know, it’s all simple. I see guys come and go left and right and it’s bad. You’ve got to appreciate everything. You’ve got to enjoy the ride until it’s the end. You’ve got to wiggle and waggle and try and make a career out of surfing or being here, you know, but the bottom line is that you’ve got to stay grateful and happy. There’s so much worse things in life you could be doing than sitting here talking to me. We’re blessed to do what we do. It’s just . . . appreciate and stay grateful and, like the kids, I try to instill in all these kids to give them a little structure in life. You know, clean up after themselves. To go do the work when the waves are flat, cuz the waves aren’t good all the time. That’s when you train. Making good choices in life. It’s all that stuff. Try to live clean. Watch out for all the fucken hanger-oners and all the bad choices that they make real easily. But only they can do it. Alls I can do is show them here’s the path, hopefully you stay on it, and if they stray off of it, hopefully they can get right back on it.”

Such a Zen thug but even if he is a Zen thug, even if he is enlightened, even if I am not seeing clearly, I know that he is still the Kaiborg of myth/reality legend and that he is greatly feared. Kaiborg stories and Eddie stories are told with equal amounts of petrified eyes and quavering voices. He is still considered a monster and I tell him and, again, he lets out a long and low “Psssssssshhhhhhhhhht” before continuing, “I don’t like that at all. But. You know what . . . . Ffffff. I created it and that’s why I’m changing it now. I’ve never been the most open and friendly guy but you know now I’m trying to like . . . this year I told myself, try to tell everybody hi. I’ll be on the bike path walking down, or on the back road, and guys will see me coming and they’ll be putting their head down and getting all squirrely and I’ll be like, ‘What’s up?’ and they’ll be like, ‘Whoooaaa.’ And I’ll be like . . . ffff, whatever. But you know, it’s life. You live and learn. You gotta go through the process and it’s a process and I wanted that . . . of course I wanted that mystique at some point, but then you’re over it and it doesn’t just end when you’re over it. I’ll probably always have it, but whatever. It serves me well cuz when I speak up they better listen. Hey, I’m not perfect. I still have my, you know, my inner demons like everybody but at least I recognize it now and I try to keep them down and don’t overreact and fly off the handle.” He laughs loudly. “I don’t want to be perceived like that anymore, though. I’m a father and a husband and basically . . . I do what I say, and say what I mean. Alls we have in our life is our word. Everything else is fucking bullshit.”

The wisdom continues to pour. The enlightenment of Kai “Kaiborg” Garcia. And it may be even greater than the enlightenment of Siddhartha Gautama “Buddha” himself because of the distance traveled. Buddha moved from spoiled rich child to enlightened one, which is a great climb, but Kaiborg moved from monster in one of the the heaviest places on earth to . . . I don’t even know. To something far greater. Wisdom. And I am feeeeeling it, baby. “Ahhhh yeah, it’s hard to make a change in your life. Super hard. Really hard. We’re creatures of habit. This guy told me a year ago, ‘You’re gonna have to change one thing about your life,’ and I really look up to that guy, and I was like, ‘Oh yeah? What’s that?’ and he was all, ‘Everything.’ And I was all, “Ffffffuuuuuuuuu.’ But he was right. You know. I did. And I’m trying to change everything. It’s not easy but I’m working on it, you know? The bottom line is we’re imperfect and it’s progress, not perfection, so if you make a little progress every day, you know, you’re doing OK. At the end of my day, I’ll sit down and think about my day and be brutally honest with myself, be like, ‘OK, how could I have made my day better? How could I have made people better around me?’ We all have our moments, but as long as I sit down there and reflect every day then I can wake up and try and make a little progress the next day. Day by day. One foot over another. It’s hard to grasp but when you start getting it, you start getting it. You start seeing what life is about, not just existing through life—you start living again. You’re not all blinded. You start looking at the ocean and the rainbows and you start seeing the leaves falling off the trees. You know, stuff like that. I don’t know. I could be fine this year and I could flip the switch next year, you know? You just never know.” Fuck sacred fig trees. Kaiborg found enlightenment under a palm.

The sun is all the way beneath the earth’s rim and the sky is on fire. It is all the colors of red and we both pause to look at it. It is, truly, paradise. But at the same time it is always truly hell. And since I am feeling all metaphysical I ask him about the hell, about Eddie and the politics of a place outside the law. I tell him that word on the Ke Nui is that Eddie and him are not on friendly terms. He stretches again and speaks, “Ahhhh we’re fine. We’re all one family. Just, everyone is on their different path. You know, I’m kinda looking for enlightenment. Just staying levelheaded. Hey, we all get along. We all argue and bicker and shit, but that’s part of it. But at the end of the day, we all got each other’s back. And the North Shore politics? You know what . . . I love this place, and politics? I could give a f—a rat’s ass, you know. I’m powerless over people, places, and things. If that guy is an asshole out there, hey, you know what, I’m not gonna worry about him. I can’t change him. I’ll let him wallow in his own shit. Just don’t bring it. Boundaries, you know? I’ve got my boundaries. Don’t, you know . . . stay out of my boundaries and it’s all good. I don’t care what you’re doing, running around being an asshole, whatever. That’s your trip. I just mind my own business now.” And I am feeling all warm and in love. He is an apologist for everything that is the North Shore. He is also validating my own personal asshole trip by not judging it. Beautiful. Love. Warm. Deluded? I don’t care anymore. Getting to the bottom of a story—selling out Eddie, Kaiborg, the North Shore—had been swallowed by a general feeling that I belong here.

At that moment an older, crazy local talking jibberish comes crashing through the Volcom house gate and into the yard. He is dripping wet, just having gotten out of the water, and is jabbering about how Pipe almost crushed him but he got fully barreled and whoosh! And bam! And pow!Kaiborg laughs at him and says, “We’re more grassroots over here. We’re more core. We have all of the local surfers come hang out here, you know what I mean? Nike down the road and Quiksilver, they have their guys and they all stay in their little bubble. They’re all bubble-ized. Over here we got guys like”—and he gestures over to the older, crazy local—“Donnie don’t go hang out at Quiksilver. You know what I mean? We got every fucken creature walking around here. We keep it real. It’s how we were all raised and we’re not fucken exclusive or . . . we’re not better and no less than anyone. It’s pretty much open arms over here.” And it is pretty much totally not but that is the way that Kaiborg feels and so I just guffaw, slightly, and tug on my pink shirtsleeve and continue to look at the fire-red sky.

The gate opens again and a young Volcom grom comes through and nods, submissively, in Kaiborg’s direction before scooting out of sight. Kaiborg doesn’t notice him but I do and ask him about the process of being a grom in the house. Standard lines about being a family and cleaning up and the dungeon and working out and living the dream because of the free bed thirty short steps away from Pipe, free food, access, and never having to fear getting beaten up in the water. But I still want to know how that came to be. How did these houses come to rule? Kaiborg listens to my question and then looks at me and then answers, “Look at me. I’m six two, two forty, you know. Surfers are fucken what? Five eight, one fifty? It’s like . . . plus I’ve trained my whole life. I’m not a normal guy, you know, so. The groms are here, they’re part of it, and they know better. If you go out there and drop in on a guy blatantly, or whatever, you’re gonna get your head slapped. But it’s mellow now. Everybody knows where they belong. It’s not like the old days.”

The old days. The old rough days, which to men like Kaiborg are over and we are all living in the soft present, and to men like Graham Stapelberg are not over because he is getting his face slapped right off, and to men like me are not over because the North Shore is scarier than any war zone. The past is always amplified but I will say that the North Shore exists in perpetual violence and it always has. Maybe the violence looked or felt different in the past but it is not less today. Only different and only realized differently.

The fire reds are turning into powder blues and darker blues. Pipeline is still thundering, shaking the Volcom deck, which shakes the cinder blocks, which shakes the couch. The contest will be running again tomorrow. Booom! And Kaiborg is gazing out and is not talking to me anymore but talking to Poseidon. “That’s a heavy wave. This place is scary.” I ask him if it still scares him and he responds honestly, “Ahhhh yeah. I want nothing to do with it.” And he says this even though he surfs Pipe every big swell. “Hey, we change. She don’t. We get older and slower. She does not let up. Every time . . . there’s a bunch of times when I been out there and I’m like, fuck . . . ” He lets his thought trail off as another wave explodes “That’s what she does out here.” Booom!

I pull myself off the couch and we shake hands and I leave him sitting there, looking out at Pipe. A Zen thug. I didn’t serve my ablution on the couch today, but I know he will still knock my head completely off if he needs to, or wants to, someday. He has been training in jujitsu for eighteen years. He has trained under the greatest mixed martial arts Brazilian master, Royce Gracie. He has fought in the octagon, or modern version of gladiator battle, many times. He is six foot two, two hundred forty pounds but seems like Gerard Butler’s King Leonidas in the film 300.

![]()