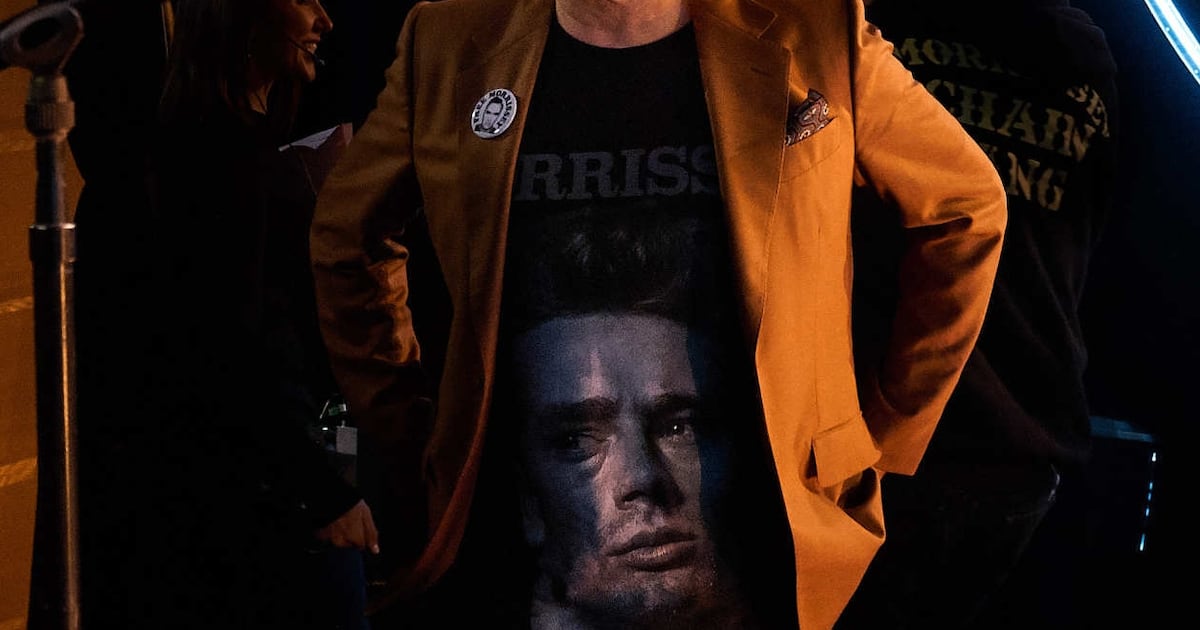

Steven Patrick Morrissey has long made a living from whinging. As lead singer of The Smiths, he could stake a claim to be that era’s laureate of complaint. The recreational grievance continued through a solo career that began months into Margaret Thatcher’s third term as UK prime minster. We Hate It When Our Friends Become Successful. There’s a Place in Hell for Me and My Friends. The song titles alone conjure up an irascible neighbour set upon ruining your afternoon in the garden.

His current volley of objections does, however, raise diverting questions about where he is going and – if it’s still okay to say so – remind the world how interesting The Smiths once were. Last week Morrissey emerged to discuss alleged efforts to suppress his most recent album. Recorded in May 2021, the sessions for Bonfire of Teenagers featured contributions from Iggy Pop (okay), Miley Cyrus (really?) and bits of the Red Hot Chili Peppers (ho-hum).

“It is almost four years old now. The madly insane efforts to silence the album are somehow indications of its power,” he told the Daily Telegraph this week. “Otherwise, who would bother to get so overheated about an inconspicuous recluse?” He goes on to allege disputes with a music-industry giant. “Morrissey has said that although he does not believe that Capitol Records in Los Angeles signed Bonfire of Teenagers in order to sabotage it, he is quickly coming around to that belief,” his website stated last year.

The sticking point is alleged to be the title track. Bonfire of Teenagers – the name alone is problematic – hangs around the attack on Manchester Arena that saw a suicide bomber murder 22 people outside an Ariana Grande concert in 2017. The song begins with a parent sending her teenager off to the gig. “Oh, you should’ve seen her leave for the arena,” he sings. “On the way, she turned and waved and smiled: ‘Goodbye’.” Less satisfactory is a later return to the line and an evocation of the subject’s death. “You should’ve seen her leave for the arena. Only to be vapourised. Vapourised!”

Another strand attacks mourners who adopted an Oasis song as lament: “The morons swing and sway: ‘Don’t look back in anger,’” he sings. “I can assure you I will look back in anger till the day I die.” Bonfire of Teenagers ends with what appears to be an ironic attack on bleeding-heart justice. “Go easy on the killer. Go easy on the killer,” he sneers. (The killer, Salman Abedi, of course, died in his own attack.)

A live version is out there on the internet, but any close analysis of the song must wait until it receives a release. Nor can we be certain exactly what is going on with the album’s spell in limbo. We can, however, say that Morrissey has lost none of his taste for weaponising bile. It is also fair to suggest he is not out just to shock, even if the lyric is likely to distress some who remember the attack.

The boldness of the provocation contrasts with one of the most memorable songs from The Smiths’ 1984 debut album. Suffer Little Children, probably the second (though some claim first) song Morrissey wrote with Johnny Marr, the band’s guitarist, addresses, in impressionistic manner, the terror that hit Manchester during the Moors Murders. From 1963 to 1965 Ian Brady and Myra Hindley killed five children and buried them on Saddleworth Moor.

Four or five years later, during my childhood, public-information films on British television were still warning kids about wandering off with strangers. In his autobiography, Morrissey noted that news of Hindley’s involvement showed “a woman can be just as cruel and dehumanised as a man, and that all safety is an illusion”.

The UK tabloids, still hopped up on the provocations of punk, flew into spittle-flecked rage at the song’s very existence. Understandably, parents of the murdered children expressed their own unease. But Ann West, mother of victim Lesley Ann Downey (mentioned by name in the tune), came around when Morrissey wrote her a letter. “She believed Morrissey was a good boy and was serious about the song and she thought it was very touching,” Scott Piering, The Smiths’ publicist, later wrote. “She was strongly on our side and really helped us.”

Returning to Suffer Little Children, one finds not just an eerie evocation of a city in thrall to collective dread but also, as in so many of The Smiths’ early songs, nods towards a greyer version of the 1960s that swinging London swept from memories. “Take me to the moor. Dig a shallow grave. And I’ll lay me down,” Morrissey sings over Marr’s minimalist chiming riff. The gloom is less mannered than in self-parodies such as Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now. The emotion is sincere. It, at least, remains uncancelled.

![]()