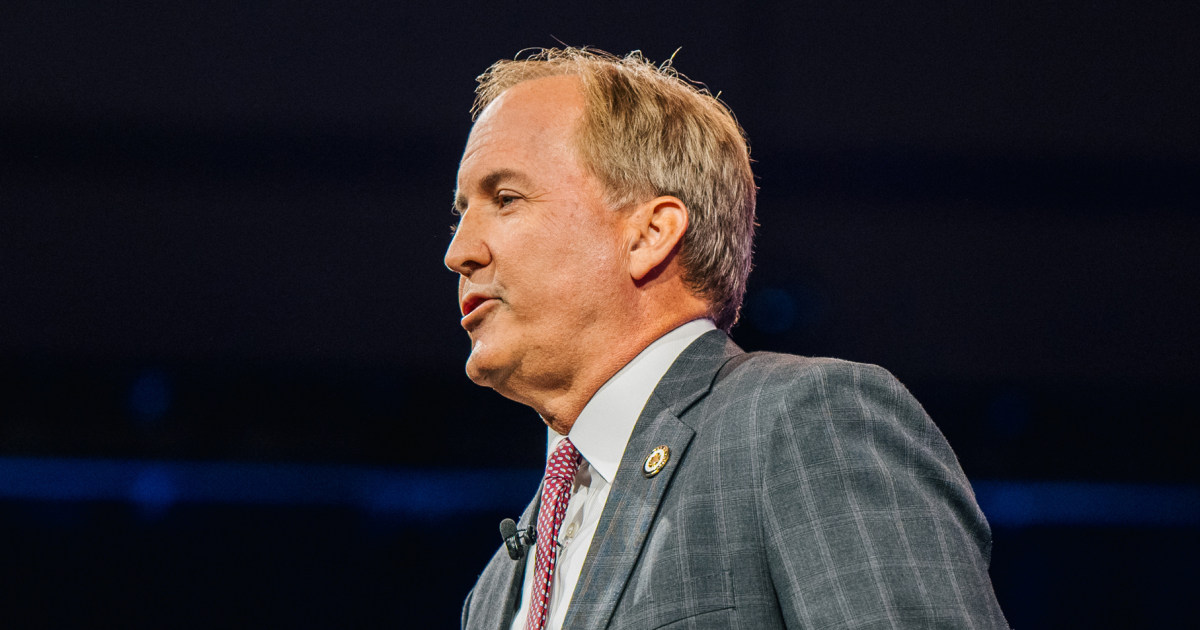

For years, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has easily ranked among the most destructively partisan and self-servingly venal elected officials in the country. And last week, he turned his sights on suppressing the votes of Texan Latinos this fall in the name of “election integrity.”

On Wednesday, Paxton’s office announced that it had carried out an undisclosed number of search warrants in several counties, including the one that houses San Antonio. The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), one of America’s oldest Latino civil rights groups, says the raids targeted several of its members. In doing so, Paxton has tipped his hand about his determination to undercut voting rights this fall — and potentially made an enemy of the very people the GOP needs to win.

Republicans have twisted the phrase “election integrity” since well before President Donald Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election.

Republicans have twisted the phrase “election integrity” since well before President Donald Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election. Rather than a dedication to ensuring that every vote is counted, the GOP has coopted it as a justification for suppressing legal votes while claiming to prevent election fraud. We’ve seen efforts in other GOP-led states set up by election security offices that have brought few charges and failed to prove widespread fraud exists.

Paxton’s latest stunt goes further, though, indicating a newfound focus on suppressing the work of an organization rather than disparate individuals. His office’s statement last week asserted that the searches were the result of a two-year investigation of supposed “allegations of election fraud and vote harvesting” in the 2022 election but did not specify the targets of the raids or why specific homes were raided. The GOP wound up winning all of the counties where the claim that was sent to Paxton originated, but they are also in south Texas, a region that showed mixed results overall in the midterms.

The second of the two potential crimes that Paxton is investigating — “vote harvesting” — is a particularly glaring sign that there’s most likely very little substance to these allegations. In using the term, the GOP tries to evoke the incredibly rare act of someone fraudulently collecting other people’s absentee ballots and casting those votes without their awareness. But in practice, Republicans are usually referring to two entirely legal practices: establishing secure ballot drop boxes or organizations’ working to ensure that senior citizens who are unable to make it to polling places have access to mail-in ballots.

The latter practice appears to be Paxton’s target, based on details reported Monday in The New York Times. Lidia Martinez, an 87-year-old living in San Antonio, who was one of the people whose homes were searched, has worked for decades helping older Latino voters register to vote. She told the Times that the officers who turned up at her house in the early morning last week were looking for voter cards that Latino residents had filled out. Finding none in their ransacking of her home, they took her laptop, her phone and other items, but not before questioning her about other LULAC members, including others whose homes had been searched.

In a news conference outside Paxton’s office Monday, LULAC’s national president accused the attorney general of seeking to “harass and intimidate Latino nonprofit organizations, Latino leaders and LULAC members” with an aim to “suppress the Latino vote.” The Latino vote in Texas has become a major driving force in determining which way the seemingly deep red state swings. Most recently, growing and increasingly diverse populations in Texas’ major cities have cut into the GOP’s dominance in statewide elections, providing narrower margins of victory in those races.

At the same time, Texas has underscored that Latinos as a group are nowhere near monolithic. Democrats’ share of Latino voters in South Texas counties near the border has dwindled in recent presidential elections, making their votes more highly sought-after. While that may seem to be contradictory with Trump’s racist policies and statements against immigrants from Central and South America, there’s no denying that his rhetoric about border security has resonated with voters there. That’s also increasingly the case in those same major cities that have been recently been seen as Democratic strongholds.

Paxton also has the comfort of knowing that he’s carrying out the will of the national GOP and its presidential nominee.

Which leads us to Paxton’s motivations in drawing the ire of LULAC with these raids. The group had never formally backed a political candidate in its 95-year history — until this month, when it endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris. Paxton hasn’t exactly been a subtle operator in the past. If his office hadn’t blocked mail-in applications ahead of the 2020 election, Paxton claimed on former Trump strategist Steve Bannon’s podcast in 2021, “we would’ve been one of those battleground states that they were counting votes in Harris County for three days and Donald Trump would’ve lost the election.” He also most likely feels emboldened to take bigger swings after the state Senate acquitted him of corruption charges in an impeachment trial last year.

Paxton also has the comfort of knowing that he’s carrying out the will of the national GOP and its presidential nominee. Trump has instructed the Republican National Committee to devote more resources to election integrity than traditional fieldwork ahead of this election. Just last week, he insisted at a rally in North Carolina that the GOP’s “primary focus is not to get out the vote, it is to make sure [Democrats] don’t cheat.”

But for the Republican plans to challenge election results in court to succeed, there needs to be a convincing case that there’s more than partisan politics at work. In targeting such a specific group and its members, Paxton may have undermined those efforts. Already, LULAC is asking the Justice Department to investigate Paxton’s efforts as a potential violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Even with years of conservatives’ narrowing the Voting Rights Act’s scope, the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division can flex plenty of muscle if it believes a state has moved to suppress a minority group’s vote. Paxton may have thought that LULAC would be easy pickings or that the searches he authorized would subdue its efforts to get Latinos to the voting booth this fall. But given the response so far, I don’t think this is the fight that Paxton wanted — or one that he has much of a chance of winning.

![]()