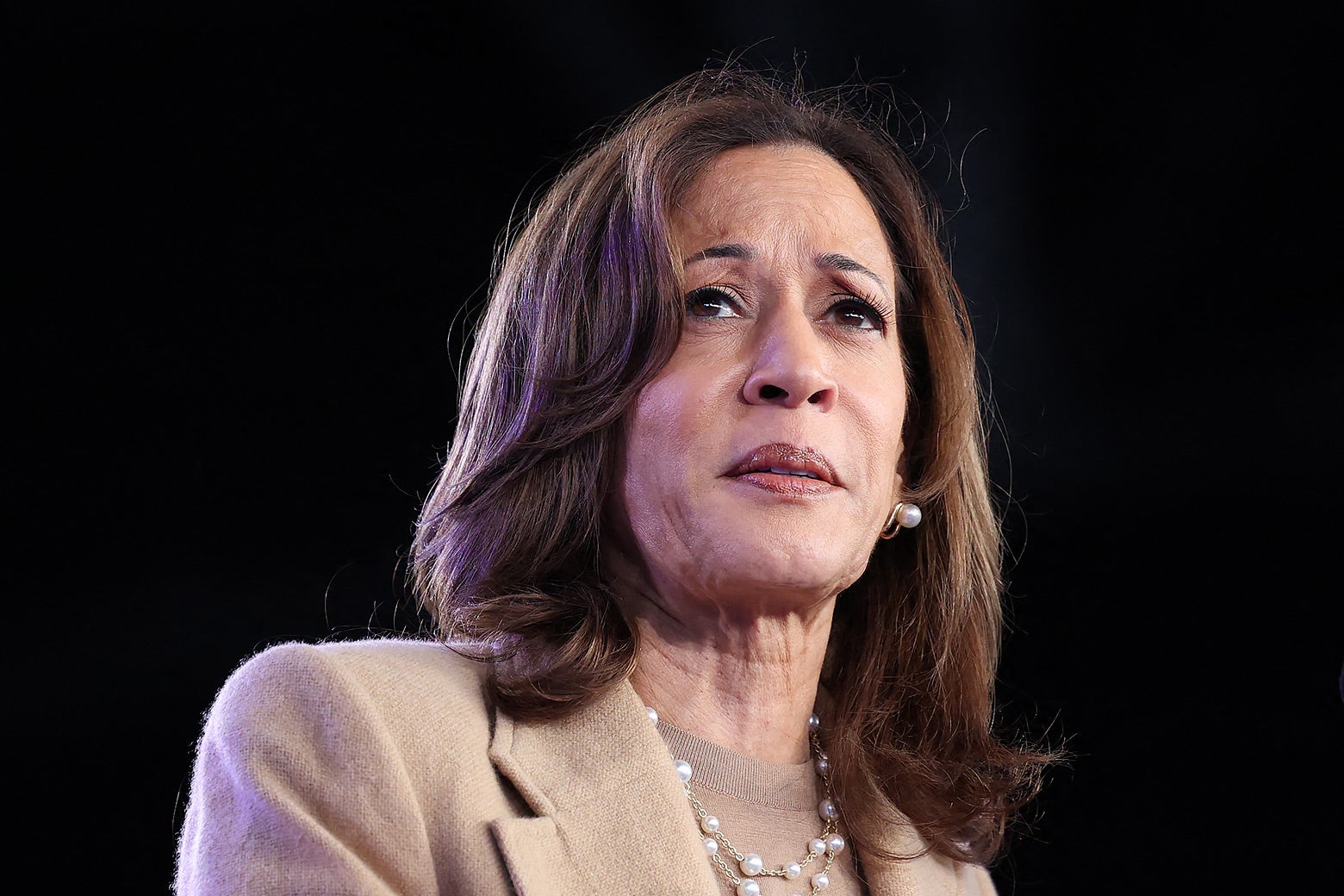

American democracy is in peril. We won’t know the exact margin of victory for some time, but the shape of the presidential contest is clear enough this morning to warrant a few basic conclusions. Donald Trump won a close but decisive victory over Kamala Harris in an election where national discontent carried the day amid record voter turnout. Trump will take office in January with an ultraconservative majority on the Supreme Court, a Republican majority in the Senate, and a likely GOP majority in the House. The era of polarized political conflict in America is not over and will surely escalate in the months to come.

The Harris campaign will receive plenty of intraparty criticism for the loss, but the widespread nature of Trump’s gains suggests an electorate broadly unhappy with the incumbent party rather than a faulty campaign strategy. Although detailed demographic data is still developing, Trump improved on his 2020 performance in rural, urban, and suburban counties, in red states and in blue states, and with white voters as well as Latino voters. President Joe Biden is the most unpopular sitting president since Harry Truman. His vice president could not escape his political gravity.

Anyone reading this website recognizes the tremendous consequence of the Harris defeat. Trump spent the campaign demonizing immigrants and repeatedly discussed turning the American military on leading Democratic Party politicians. His own former chief of staff has described him as a “fascist,” and over the summer, the Supreme Court shielded Trump from prosecution for any crimes committed in the course of “official acts” as president. The past eight years offer little reason to hope that leaders in the Republican Party will check Trump’s most reckless impulses, and every reason to expect Trump support from billionaires and big business. The best Democrats can hope for over the next four years is chronic dysfunction and administrative incompetence. The worst is frightening to contemplate.

Incumbent political parties are struggling across the world. Liberal and conservative governments on multiple continents have been suffering electoral setbacks over the past year as they grapple with a variety of global economic dislocations in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Japan has slipped in and out of recession, while Europe is plagued by weak growth. The U.S. economy remains very strong—the envy of the developed world, with inflation tamed, growth robust, and the best labor market in 50 years. But voters have consistently reported economic dissatisfaction in surveys all year.

The country is plainly unhappy, whatever the metrics say, and none of the Harris campaign’s appeals to democracy, personal character, or abortion rights were enough to secure gains for her among the constituencies the campaign targeted. No rush of suburban women for Harris materialized; no apostate Republican bloc followed Liz Cheney into the Harris camp. Trump even appears to have enjoyed a surge of support among Latino voters as he championed mass deportations.

Trump’s was a campaign of raw anger, and voters across the country rewarded him for it. Americans have been living in an era of political anger since the bank bailouts of 2008, but the Democratic Party has not. Its legislative successes—Obama’s health care law, Biden’s green tech investments—have been narrow procedural affairs, negotiated through mastery of Capitol Hill process rather than the mobilization of public energy and emotion. Anger will remain the dominant currency of American politics in a second Trump term, as Trump nurtures the very forces leading to so much anxiety and instability. Silicon Valley billionaires will pad their profits by spewing hate online, various parts of our government will be effectively up for sale to lobbyists and contractors, oppressive regimes abroad will be emboldened to attack their neighbors, and Trump himself will relentlessly attack journalists.

In difficult times, optimism is a duty, not an indulgence. Imperiled as it is, American democracy is not dead. Trump was a profoundly unpopular president, and will be again. There will be political battles worth fighting and political victories to be won if the Democratic Party can reshuffle the demographic deck. The trend across the 21st century has been for Democrats to consolidate advantages with college-educated voters while losing support among voters without a college degree. That can’t continue in a country where most voters don’t graduate from college.

I don’t know how much of that process has to do with actual policy commitments. Trump’s vacuous, victorious campaign offers little evidence that voters are responding directly to policy ideas. But Democrats will have to find a way to channel the prevailing public anger instead of attempting to bypass or assuage it. Angry people don’t have much faith in win-win outcomes—somebody has to lose for them to win. Democrats need to learn how to craft political narratives with active villains who must be held accountable. Trump defines his coalition by defining his enemies—he hates immigrants, so if you’re not an immigrant, he’s on your team.

Where Trump offers cheap scapegoating, Democrats must instead revive a politics of public accountability. Throughout the 21st century, Democrats have practiced a deep aversion to open conflict with bad actors. Obama did not even bother to pardon the torturers from the George W. Bush administration, eventually working to suppress reports of the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation” operations. After the financial crisis of 2008, banker bonuses were protected with public funds, while plainly criminal financial conduct went unprosecuted as the bank crash delivered the worst recession since the Great Depression. In Trump’s first term, Nancy Pelosi shrank from confronting him over obvious misconduct.

In each of these iterations, party leaders issued vague political considerations, fearing to alienate Republicans in the public at large. But at a certain point, the pattern looks like a simple fear of confrontation itself. Democratic leaders could not even bring themselves to move an obviously diminished Joe Biden out of the race until it was too late, instead attempting to deceive the public about the state of his decline while hoping for the best. The public feels stripped of agency, subjected to social forces beyond its control, from the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, to the financial crisis to the COVID-19 crash. By refusing to defend basic accountability, Democrats have deepened the very divides they hoped to paper over.

Democrats insist they are fighting for democracy and the public interest, but they have a hard time defining whom and what they are fighting against. It’s time to figure that out. The future of democracy depends on it.

![]()