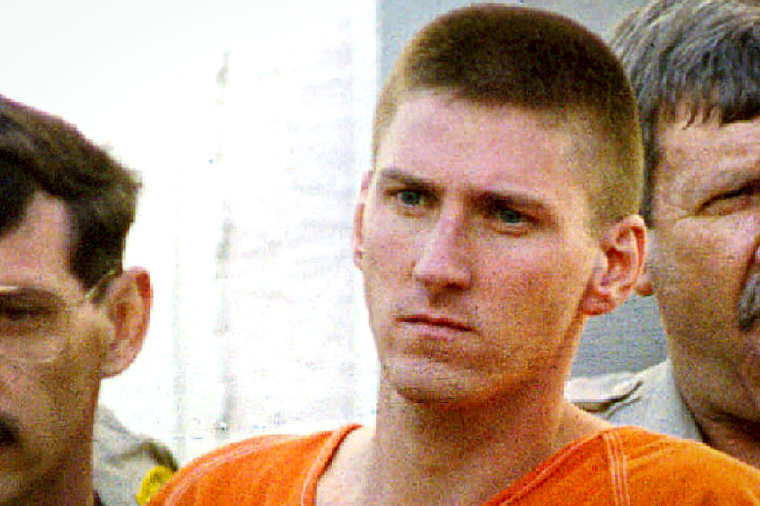

Twenty-nine years after killing 168 people in the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City — the deadliest act of domestic terrorism in U.S. history — Timothy McVeigh is dead and buried.

But the extremism that fueled his hate on April 19, 1995, is alive and unencumbered in today’s conservative movement.

But the extremism that fueled his hate on April 19, 1995, is alive and unencumbered in today’s conservative movement.

In many ways, McVeigh embodied the threats of political violence and radicalization presently gripping conservatives — and thus, the rest of the U.S., too. I think of McVeigh as connecting the eras of white domestic terrorism that characterized the 20th century and the more recent strain of extremism infecting the MAGA movement.

In 2018, for example, historian Kathleen Belew wrote that the Oklahoma City bombing ought not be seen as the act of a “lone wolf” but, rather, in its proper context:

In fact, the bombing was the outgrowth of decades of activism by the white-power movement, a coalition of Ku Klux Klan, neo-Nazis, skinheads and militias, which aimed to organize a guerrilla war on the federal government and its other enemies.

McVeigh, who was executed in 2001, wasn’t a lone wolf. He was one among a pack. And his death appears only to have spawned other extremists.

An ABC News report in 2020 cited FBI records showing that several people who’d been arrested in the three years prior for suspected links to domestic terrorism or violent white supremacy had been known to make references to McVeigh.

In 2017, the Southern Poverty Law Center reported on a disturbing trend of “McVeigh worship” playing out in extremist circles.

And during a Democratic-led House hearing two years ago on the trend of veterans embracing violent extremism — as was the case during the Jan. 6 insurrection — the Oklahoma City bombing’s toxic influence as a source of inspiration came up, as well. (McVeigh was a decorated veteran of the Persian Gulf War.)

Even in Oklahoma, where one would hope that the memory of the 1995 bombing would deter potential copycats, the threat of other attacks seems to loom large.

Last summer, after right-wing activist Chaya Raichik’s popular social media account shared a video targeting a school librarian, a Tulsa-area school district was targeted with bomb threats for six days straight.

The video was promoted by Oklahoma’s schools superintendent, Ryan Walters, who in January awarded Raichik with a job as an adviser who will have a say in what content is deemed appropriate for school libraries.

And I think that’s a perfect example of how intractable the problem of far-right extremism has become in this country.

Nearly 30 years after McVeigh’s deadly bombing, Republicans — even those in Oklahoma — seem to have learned the wrong lessons. Instead of rejecting violent extremism and rooting it out of their ranks, they’ve just devised ways to use it to their advantage.

![]()